Why do we think less about some purchases than others?

Mental Accounting

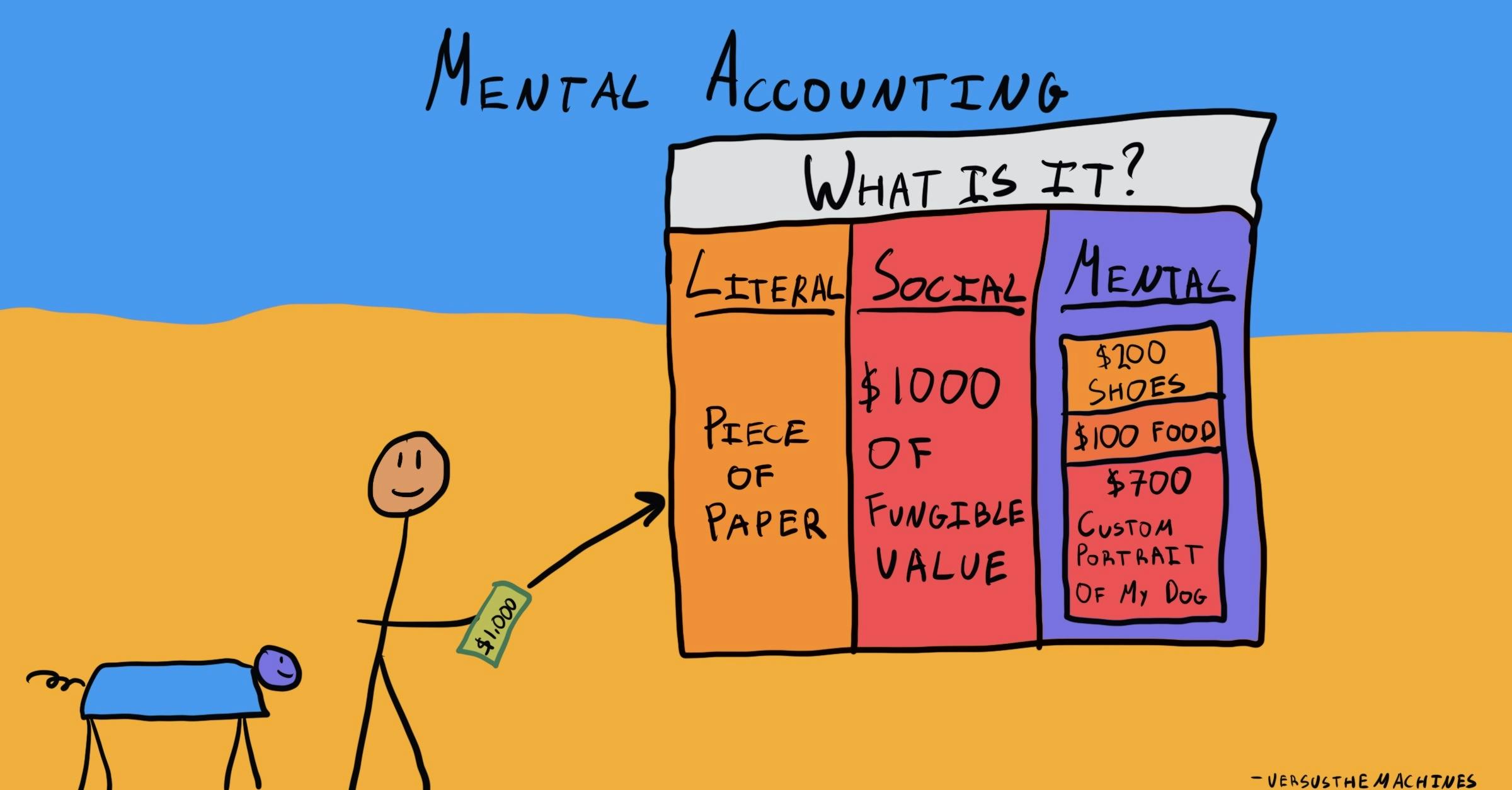

, explained.What is Mental Accounting?

Mental accounting explains how we tend to assign subjective value to our money, usually in ways that violate basic economic principles.1 Although money has consistent, objective value, the way we go about spending it is often subject to different rules, depending on how we earned the money, how we intend to use it, and how it makes us feel.

Where this bias occurs

Imagine you’re walking down the street, and you happen to find a $100 bill lying on the sidewalk. Ordinarily, you’re a pretty frugal person, and you’ve been trying to save some money to put towards buying a car in the future. Today, however, you take your newfound $100 and put it towards an expensive dinner. You tell yourself that this money isn’t “car money” — this is a one-off, special occasion, so why not treat yourself to a nice evening out?

Related Biases

Individual effects

Because of mental accounting, we often behave illogically when it comes to money. We don’t think as carefully about buying something if we’ve already earmarked some amount for this purpose; we fail to consider the “big picture” of our financial situation; and we respond differently to gaining or losing money, depending on how the situation is presented to us. Mistakes like these cause us to overspend and sabotage our efforts to save up.

Systemic effects

On top of leading us to budget poorly, our habit of mental accounting can be easily taken advantage of by marketing companies. Tricks such as offering “bonus” gifts, or pushing “extras” on top of big purchases, are effective because of the cognitive biases that are involved in mental accounting. Mental accounting also fuels the sunk cost fallacy, which can cause us to persevere with a behavior or endeavor for longer than we really should.

Why it happens

There are several reasons that our mental accounting processes lead us to make bad decisions about money. These reasons are all rooted in the fact that people do not think of value in absolute terms. Instead, an object’s value is relative to various other factors.2

We give money mental labels

One of the core properties of money is that of fungibility, meaning that it is made up of units that are all interchangeable and indistinguishable from one another. Money is fungible because a dollar is worth the same no matter where it came from or how it is spent. Additionally, money doesn’t come with any labels; the same dollar that you put towards your morning coffee could also be spent on a bus ticket, or put towards a new dress.

In mental accounting, however, we tend to treat money as less fungible than it is.2 This can be thought of as filing money into different mental bank accounts that we apply different rules to. There are many ways people go about categorizing money. Often, money is put into “accounts” based on where it came from. Many studies have shown that people tend to label additional income either as “regular income” or as a “windfall gain.” (The above example about finding $100 randomly is an example of a “windfall.”) What’s more, people are more likely to spend windfall gains than regular income—and are more likely to spend them on luxury goods than essential ones.3 Even though there is nothing different about money received unexpectedly compared to money from any other source, we feel like it’s special, so we feel justified in spending it extravagantly.

Money is also often labelled based on its intended use. An interesting example of this comes from a study on gift card use. When people receive gift cards for a specific retailer, they tend to use them on items that are highly representative of that retailer. For example, when using a gift card at a Levi’s store, people are more likely to buy a pair of jeans, which Levi’s is famous for, than something like a sweater, which is not specific to Levi’s.4 The researchers argue that this is because people have put the gift card into a mental account for that specific store, so they feel compelled to spend it in a way that is congruent with the brand.

Our idea of a “good deal” depends on the situation

It is common knowledge that there are certain venues where one can expect to pay much more for the same product than one would elsewhere. For example, when seeing a movie in the theatre, most film goers know they will have to pay significantly more for a pack of M&M’s than they would at a convenience store. The same goes for many other venues, such as sporting events, concerts, or amusement parks. Often, the expectation that one will pay exorbitant prices for basic goods has become an accepted part of a broader experience: yes, a simple hotdog costs $10 when you’re buying it from a vendor during a baseball game, but that’s just how these things always are, and eating while you watch is part of the fun!

Why are we so willing to pay for goods that we know are overpriced? The answer is rooted in the fact that, when we buy something, we don’t just care about the objective value of the thing we’re purchasing; we also care about whether we’re getting a good deal. This concept is known as “transactional utility,” meaning the merits of the transaction itself.1

Transactional utility can have a major influence on our willingness to pay for something. In one experiment that looked at transactional utility, participants were split into two groups and asked to imagine themselves lying on the beach on a hot day, craving a ice-cold bottle of their favorite beer. (The researchers made sure all participants were regular beer drinkers.) In this scenario, a friend volunteers to go and fetch some beer from the only place nearby that sells it. For one group, the vendor was a “fancy resort hotel”; for the other, it was a “small, run-down grocery store.” The friend asks how much the participant is willing to pay for beer, and says he will only buy it if the beer costs as much or less than the price they give.1

The groups responded with very different numbers: while the median answer for the hotel group was $2.65, the median for the grocery store group was $1.50. (This study was done in 1985, so those figures aren’t as low as they sound—in 2020 US dollars, they’re equivalent to $6.35 and $3.59, respectively.)

This result is especially interesting, considering that in this hypothetical scenario, both groups would end up consuming their beer in the same place: on the beach. Ordinarily, places like “fancy hotel resorts” might be able to justify higher prices by arguing that they provide a luxurious “atmosphere” for their customers—but the participants in this study were still willing to pay a premium, even without being able to enjoy that atmosphere.

The main take-away from this experiment is that our definition of a “reasonable” price is flexible, depending on the situation. If we were only concerned about objective value, we likely wouldn’t be willing to shell out nearly $3 extra to drink the same beer in the same place. But transactional utility, or getting a “good deal,” can alter our judgment.

We perceive gains and losses differently depending on their framing

In a study by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, two of the most influential figures in behavioral economics, participants were told to imagine they were about to purchase a jacket for $125 and a calculator for $15. The calculator salesman then informs the buyer that the same calculator is on sale for $10 at a different branch of the store, which is a 20 minutes’ drive away. 68% of respondents said that they would be willing to make the drive to save $5 on the calculator.

However, with another group of participants, the question was altered: now, the calculator costs $125, and the jacket $15. The calculator is on sale at the other branch for $120. In this case, only 29% of respondents said they would make the trip. In both scenarios, the amount of money being saved is the same.5

These different patterns of behavior are related to framing effects, which were first described by Kahneman and Tversky. Their work, and many others’, has shown that the way an option is described can have a major impact on our decision-making.

The scenario described in the calculator study is an example of a “topical frame”: the situation is worded in terms of the price of the calculator.5 This causes people to perceive the gain of $5 relative to the base price of the calculator. When the calculator ordinarily sells for $15, getting $5 off seems like a great deal, but $5 off a $125 seems like a much smaller gain.

Another factor that affects how we perceive losses and gains is whether they are integrated or segregated—in other words, whether they happen altogether, or are spread out over separate events. Consider the hypothetical example of Mr. A and Mr. B, who have been given some lottery tickets. Mr. A wins $50 in one lottery and $25 in another, while Mr. B won $75 from a single ticket. Who do you think is happier?

When participants in a study were asked this question, 56 said Mr. A would be happier, 16 said Mr. B., and 15 said they would be equally happier. Even though both men come away with the same amount of money, a large majority of people agreed that two smaller wins would make somebody happier than a single, larger one.

However, the opposite is true for losses. In another hypothetical scenario, Mr. A finds out some mistakes have been made on his tax return, and he owes $100 to the IRS. Later that same day, he receives a separate letter informing him he also owes $50 on his state income tax. Meanwhile, Mr. B receives one letter from the IRS, informing him he owes them $150. Again, the amounts of money are the same; and yet, the majority of study participants said that Mr. A would be more upset by these events.

These examples show that people are generally happiest when gains are segregated and losses are integrated. Even if the outcome is the same, we respond very differently depending on how things are presented. This tendency can be taken advantage of by companies trying to separate us from our money. For instance, when buying something expensive like a new car, salespeople often try to tack on “extras,” such as paint protection and entertainment systems. Because these smaller losses are integrated into the much bigger loss of buying the car itself, we don’t feel like it’s such a big deal, and are much more vulnerable to springing for additions we don’t need.1

Why it is important

In general, mental accounting alters our perception of our finances, and makes it easier for us to overspend. It also makes us susceptible to marketing companies looking to make us spend more.

Mental account and marketing tactics

As the beer experiment described above showed us, the perceived transactional utility of an item (in other words, whether it’s a good deal) depends on the context, and on our past experience: participants in that study had learned that fancy hotel bars charge more for beer, and so they were prepared to pay more for it. Advertisers often try to capitalize on this by promoting their products as high-end, luxurious options, or by trying to associate them with some special occasion. For example, in the 1980s, the beer brand Michelob was well-known for its slogan, “Weekends are made for Michelob.”1 The goal is to leave customers feeling like the occasion itself is a good enough excuse to indulge in the product—and also willing to pay a premium for it.

Mental accounting gives us a narrow view of our own finances

When it comes to setting budgets for ourselves, mental accounting can lead us astray by having us think in terms of separate accounts, rather than consider our financial situation holistically. For example, one might have a mental “coffee” account, for which we mentally budget a certain amount each week for a daily latte from Starbucks. On the one hand, this mental accounting can save us time and energy: we don’t have to go through a decision-making process every single day and try to calculate whether a latte still fits into our budget. However, one we’ve set up a mental account for coffee, we stop thinking critically about whether we really need to direct so much money at this purpose, or whether we are paying a reasonable price for it—it just becomes a given.6

Filing our money away into different mental accounts also blinds us from seeing that some of our money might be put to better use elsewhere. As an example, people such as servers or baristas, who receive tips at work, may engage in mental account when they view their tip money is “free money,” exempt from the rules they would apply to their normal income.6 This way of thinking can be a barrier to saving up or paying bills on time.

Separate “accounts” make us feel like things are less costly than they are

Finally, mental account contributes to the sunk cost fallacy—the tendency to continue with a behavior for longer than we should, because we feel like we need to make our initial investment “worth it.”7 For example, let’s say you’ve spent $100 on a concert ticket, which you bought several months in advance. On the day of the concert, turn ends up being a blizzard, making it very difficult and unpleasant for you to get to the venue—arguably so much so that it outweighs your excitement for the show itself.10 Do you still drive to the concert?

In this situation, many people would feel compelled to make the trip through the blizzard, because otherwise, it would feel like the $100 spent on a ticket has been “wasted.” In reality, the $100 is a sunk cost: it is spent, and no matter what you do, you will still be out $100. If the costs of getting to the concert venue are greater than the pleasure you will get from seeing the show, then at the end of the day, going will result in a worse outcome than staying home.

This behavior can be explained in terms of mental accounting. If you’ve opened a mental “account” for the concert, after you’ve bought the ticket but before you’ve seen the show, it’s like the account is overdrawn $100. If you were to stay home, you would need to close the account with a negative balance, making you more aware of the loss. By going to the concert, however, you feel like you got what you paid for, and the negative balance has somehow been paid off.8

How to avoid it

Mental accounting can distort our perceptions of money and lead us to spend based on intuition, rather than reason. Luckily, by making a concerted effort to break these bad financial habits, it is possible to prevent yourself from making these mistakes. The best thing you can do to avoid mental accounting is to be deliberate with your money: think critically about your spending habits, and honestly ask yourself if there is any room for improvement.

Create a household budget

Instead of just keeping mental tabs on how you spend your money, it can be helpful to make an outline of all your expenses, and how much you would ideally spend in each category. There are many online budgeting tools to help with this.

If drawing up a whole budget right away is too daunting, just start by tracking your normal spending for a month: make a note anytime you buy something, as well as when you receive any income. By putting numbers to your financial situation, you might be able to see it in a different light. It might not feel like a big deal to pocket all your tips as “free money,” but when you’re keeping track, you may realize that that cash adds up more than you thought it did.10

Make a plan for unexpected income

Windfalls gains often end up being spent on spur-of-the-moment purchases. Tax returns are a good example: even though we know to expect a tax return every year, we never know exactly how much it will be, and therefore can’t specifically budget for it. Then, when we do receive that money, it feels like “extra” cash, and becomes easy to spend all at once.

To avoid this, figure out a strategy for unexpected income, like tax returns, gifts, and bonuses. For example, one might decide to put half of that tax return money into a savings account, and spend half on a treat of some kind.10

How it all started

Mental accounting was coined by the economist Richard Thaler, and was heavily influenced by the work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. The three men often collaborated with each other, and produced bodies of work that went on to define behavioral economics as a field.

Before Thaler, Kahneman, and Tversky, standard economic theory was based on the assumption that consumers behave rationally. Thaler criticized this body of theory for being prescriptive rather than descriptive: it prescribed behaviors that the ideal consumer “should” follow, rather than describe how real people actually act.1

In several papers, Thaler detailed how mental accounting errors led people to violate many important rules of economic theory—for example, the principle of fungibility. Framing effects and the sunk cost fallacy are other examples of how consumers behave irrationally. Importantly, in line with the work of Kahneman and Tversky, Thaler demonstrated that the errors people make are not random; instead, they are “predictably irrational.” Thaler’s work him to win the Nobel Prize in economics in 2017.11

Example 1 - Credit card spending

It has long been suspected that paying with a credit card, rather than cash, encourages people to spend more money. This suspicion turns out to be supported by evidence: studies have indeed found that people are more willing to pay if a credit card is used, even if they have to pay a large fee to use the card.12

One of the main reasons for this is something called payment decoupling, or the separation of the purchase from the payment. Credit cards decouple payments in multiple ways. For one, they delay the actual payment until sometime much later than the purchase (i.e. whenever the credit card bill is due). Even more importantly, payments made with a credit card are less alien, or noticeable, to us. These payments feel “separate” because we barely register them when we are making them; in fact, research shows that people have worse memory for purchases made by card than purchases made by cash.8

Another reason has to do with the integration of losses. As discussed above, we tend to be less upset by losses if they happen all at once, rather than being spaced out. Credit cards play to this by combining many expenses into a single bill. When we’re out shopping, it is often less painful to pay for something by card because, compared to our total credit card bill, this one charge seems relatively small.8

Example 2 - Time of purchase

When we buy something that we don’t intend to use right away, mental accounting can make that expense feel smaller than it would otherwise. This is because we tend to think about these purchases as “investments,” rather than normal spending. On top of that, whenever we eventually do consume the product we bought in advance, we feel like it’s “free” because we paid for it so long ago.13

One example of this mentality in action comes from a paper written by Thaler & Shafir (2006). One of the authors opens the paper by talking about how, when he moved into his house, it came with a stove that he needed to get rid of. In the end, he made a deal with the owners of a local cafe, giving them the stove in exchange for a stack of coupons to their shop. Even though the coupons each had a designated worth—$5—and had come at the expense of the stove, the author says that the baked goods and coffee he was able to buy with them felt “free.”

Had the cafe owners simply paid with cash rather than coupons, and the author had paid for his breakfasts with that cash instead of with coupons, it is doubtful that he would still have felt like he was getting something for free. But because the coupons had been purchased in advance, their cost didn’t seem to be associated with his purchases.

Summary

What it is

Mental accounting is our tendency to mentally sort our funds into separate “accounts,” which affects the way we think about our spending. Mental accounting leads us to see money as less fungible than it is, and makes us susceptible to biases such as the sunk cost fallacy.

Why it happens

Mental accounting happens mostly because we perceive the value of objects relative to other reference points, rather than in absolute terms. When we are making decisions, the way our options are framed can also impact our perceptions of them.

Example #1 – Credit cards

Mental accounting makes it easier to spend money by credit card because of a process known as payment decoupling: the payment feels “separate” from the thing we are purchasing, and we register it less. This effect is also due to the fact that credit card bills integrate many costs together, which is less upsetting to us than facing them separately.

Example #2 – Advance purchases

When we buy something in advance, we think of it more as an “investment” than as typical—but when we eventually consume the thing we bought, we still don’t register the cost.

How to avoid it

The best way to avoid mental accounting mistakes is to have a budget, and to watch your spending more closely. Having a plan for how to deal with unexpected income can also help to avoid blowing this money on unnecessary items.

Related TDL articles

Time Is Money: How Mental Accounting May Influence What We Spend Our Time On

This article explores how the idea of mental accounting can also be applied to time management. Just as we label money depending on its source and purposes, we also have a habit of labelling blocks of time and treating them differently. This might hinder our productivity and be detrimental to our wellbeing in the long run.