MINDSPACE Framework

What is a Framework?

Behavior change frameworks are the bedrock of applied behavioral science. Designed by behavioral scientists for policy makers and industry leaders, these summaries of cutting edge decision-making insights are essential for applying research in the public and private spheres. Frameworks distill strategies for influencing human decisions into simple, portable mnemonic devices or acronyms. This makes it possible for complex, theoretical insights about how people think and act to make their way into the practices of organizations across every industry and environment. To understand more about how these frameworks work in practice, check out our case studies.

Theory, meet practice

TDL is an applied research consultancy. In our work, we leverage the insights of diverse fields—from psychology and economics to machine learning and behavioral data science—to sculpt targeted solutions to nuanced problems.

The Basic Idea

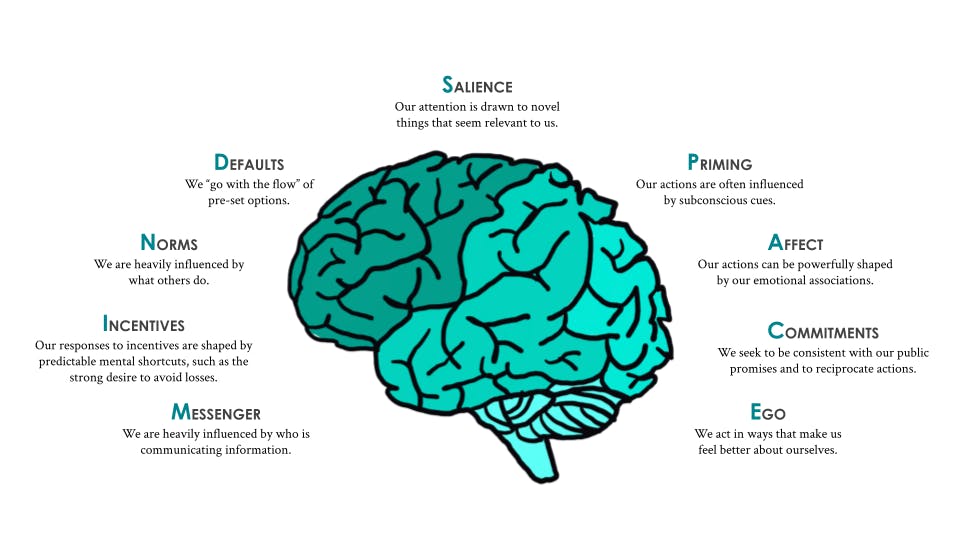

MINDSPACE is a framework that focuses on nine forces that drive behavior across a variety of contexts.1 MINDSPACE is not an alternative to current policy making methods, rather, it complements them to integrate behavioral science into the process. The creators of the framework recognize that the public shapes the usage of such behavioral change tools. MINDSPACE has been supported by both field and laboratory research from behavioral economics and psychology. The nine effects are thought to have the most robust significance on automatic processes of judgement and influences, and are outlined below:

| Messenger | We are heavily influenced by who is communicating information. |

| Incentives | Our responses to incentives are shaped by predictable mental shortcuts, such as the strong desire to avoid losses. |

| Norms | We are heavily influenced by what others do. |

| Defaults | We “go with the flow” of pre-set options. |

| Salience | Our attention is drawn to novel things that seem relevant to us. |

| Priming | Our actions are often influenced by subconscious cues. |

| Affect | Our actions can be powerfully shaped by our emotional associations. |

| Commitments | We seek to be consistent with our public promises and to reciprocate actions. |

| Ego | We act in ways that make us feel better about ourselves. |

Key Terms

Behavioral economics: The study of how people make economically-motivated decisions.

Behavioral government: Refers to governments who draw on behavioral economics to adopt a realistic view of human behavior. It is believed that stronger policy can be developed through an understanding of how biases and heuristics influence people’s decisions.

MINDSPACE: A mnemonic for the nine effects on human behavior, used to explain and intervene in a variety of subject areas: messenger, incentives, norms, defaults, salience, priming, affect, commitments, and ego.

History

MINDSPACE was one of the first behavioral frameworks to be applied in a policy-making context, laying the groundwork for what has since become a major trend in countries around the world. The development of this framework started with an initiative by members of the UK Cabinet Office to study the implications of behavioral theory for policymaking.1 The Institute for Government, a UK think tank, was commissioned to create a report on the subject, alongside academics from the London School of Economics and Imperial College.

The goal of the report was to explore the application of behavioral theory to public policy, for use by senior public sector leaders and policymakers. The report was intended to play a key role in a program designed to build the capacity for behavioral economics across the UK Civil Service. They grounded their work in interviews with academics, behavior change experts, and senior civil servants to tie expertise to the applied context of policy-making.

Creators of the report recognized that most traditional public policy interventions assumed that people would analyze all information they receive and act in ways that reflect their best interests, therefore operating under the “reflective mind.” However, the creators were more interested in shifting the focus away from concrete facts and information, and towards altering the social context in which people act, where they are influenced by their “automatic mind.” Importantly, the creators acknowledged that people sometimes make irrational choices, and wanted to assess the factors that influenced them. This endeavour set the stage for studying and exploring the nine factors (MINDSPACE) that influence behavior.

Researchers believed that policymakers could better target their interventions if they were aware of, and accounted for, such biases and heuristics. The MINDSPACE report was published on March 2, 2010, by the Institute for Government and the Cabinet Office. Publication of the comprehensive report resulted in the creation of the Behavioural Insights Team and popularized the framework of nine robust, non-coercive influences on behavior.

Important Actors

The Institute for Government

The leading UK think tank, The Institute for Government offers a space to help civil servants and senior politicians bring about change.3 It provides research and analysis, topical commentary, and public events to explore the key challenges facing government. Members of the Institute for Government pioneered the MINDSPACE report.

The Behavioural Insights Team (BIT)

Also known as The Nudge Unit, BIT is a UK-based group that aims to improve lives and communities.4 BIT works with governments, businesses, and charities to tackle major policy problems. The team was formally established after the publication of the MINDSPACE report in 2010, based on the seven-person team that worked with the UK government. At its creation, BIT was the world’s first government institution dedicated to applying behavioral sciences to policy. BIT continues to use the MINDSPACE report as a framework to improve policies and public services.

Consequences

The MINDSPACE framework has built the capability for behavioral theory to be used effectively in government.1 As a result of this framework and others like it, governments around the world increasingly use behavioral insights to design and enhance their policies and services.

In 2018, the BIT published a report entitled “Behavioural Government: Using behavioural science to improve how governments make decisions.” 3 This report builds on the MINDSPACE report by acknowledging that government officials and ministers are influenced by the same heuristics and biases their work aims to address. The report explores how this happens and how such biases can be mitigated by focusing on three core areas of policy making:

- Noticing refers to how information and ideas enter policymaker agendas, through framing effects (the way an issue is presented) and confirmation bias (the tendency to seek out evidence that supports one’s views).3

- Deliberating refers to how policy ideas are developed. While group discussions are central to policy making, the illusion of similarity convinces us that others share our beliefs, which can make policymakers overestimate the extent to which people will understand or accept a policy. Further, inter-group opposition can result in rejecting sound arguments on the basis that they come from other groups, and group reinforcement can result in self-censoring or conformity.

- Finally, executing refers to how policy intentions are translated into action. Optimism bias can cause policymakers to overestimate their abilities, while the illusion of control can cause policymakers to overestimate how much control they have over certain events.

Acknowledging the biases associated with noticing, deliberating, and executing during the process of policymaking, the “Behavioural Government” report provides targeted suggestions to combat each issue.3 The report does a deep dive into each of the biases and strategies for improvement and highlights why all parties should care about a behavioral government. MINDSPACE was one of the first attempts to fuse behavioral science and public policy. It has fueled the impressive work done by the BIT since its inception, which has touched clients in the UK and around the world.

Frameworks such as MINDSPACE, which “nudge” people in certain directions, have attracted the attention of academics and policymakers.2 However, there is concern over how long the effects of these policy changes last. Some effects appear to be fleeting, such as those of priming, since they may only last for a short while after exposure to the prime. This presents an uncertainty, since the level of impact may not be fleeting. Although the effects of priming may only be activated for a short interval, they can effectively change a behavior or decision. If priming can influence someone to make a commitment that results in sustained change, then priming can be thought of as a “trigger.” On the other hand, some effects may be more self-sustaining: defaults are based on the “status quo”, which are likely to encourage stability over time. To this end, there has also been concern over the lack of practical evidence regarding how the effects may develop over time, to the extent that they actually influence change.

One objective of the MINDSPACE report was to help the UK government become a behavioral government.1 However, as mentioned, the idea of a behavioral government has been criticized because government officials are themselves subject to such biased influences they aim to address.5 This idea was acknowledged by the BIT and resulted in the “Behavioural Government” report mentioned above.

Further related to the idea of a behavioral government are critiques of libertarian paternalism. Essentially, libertarian paternalism refers to the idea that it is possible for institutions such as governments to influence behavior for the better while also respecting freedom of choice.6 Examples of criticisms regarding libertarian paternalism surround the configuration of new kinds of state and citizen identities: specifically, certain kinds of policies promoted by such governments infantilize citizens.7 Rather than promoting the well-being of citizens, some critics believe freedom is actually robbed as institutions impose their own values and agendas onto the public.8 9

Case Study

Safety: Reducing gang violence

A series of initiatives against gang violence have resulted from public fear of increasing crime rates associated with gangs.1 Further concern has extended to the prevalence of gang membership within people aged 10 to 19 years. In the case of gang violence, the two MINDSPACE factors of messengers and norms can be used to change behavior. Specifically for messengers, people are strongly influenced by the behavior of those they perceive to be similar to them. Applied to the topic of gangs, if behavior is widely practiced by peers and therefore becomes a norm, others will hope to be affiliated with gangs to conform.

An American approach called the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence (CIRV) depends on making one gang member’s actions affect all other members.1 If a member commits a crime, the whole group bears the consequences. CIRV also involves gang members in face-to-face forums that draw on wider social norms, by having victims’ relatives, ex-offenders, and members of the local community speak on the impacts of gang violence. Related to the messenger effect, such messages are most effective when relayed by figures the gang members respect.

Ceasefire, a program first launched in Boston in 1996, was based on the CIRV model.1 At its onset, the US National Institute of Justice found that the intervention reduced the average number of monthly youth homicides by 63%. Another evaluation of a similar program found that shootings and killings dropped by 41% and 73% in Chicago and Baltimore respectively, and that declines between 17% to 35% were attributable to Ceasefire alone. In Cincinnati, gang-related homicides fell by 50% in the first nine months of program implementation. Thus, the improvements in gang affiliation and behavior seem to endure across time, such that once the social norm is embedded - with the help of an influential messenger - it becomes self-sustaining.

Sustainability: Increasing recycling

Recycling rates have been found to be markedly lower in the UK compared to other countries in Western Europe, so the UK government felt the need, in 2007, to improve recycling policies and habits.1 For this particular intervention, the two MINDSPACE factors of incentives and loss aversion have been used. Deposit schemes have been used in many countries to encourage people to return empty packages and have been linked to reductions in littering. The basic principle is for customers to pay an additional fee when purchasing bottles or associated packaging, which acts as a deposit that is returned when the empty packaging is brought back. To this end, deposit schemes are an example of loss aversion as the desire to ‘not lose’ the extra fee incentivizes people to return their packaging. In a 2010 survey, 82% of UK residents said that they would support a deposit scheme of five pence per drink container.

As for incentive schemes, there have been examples in the UK that have improved recycling rates.1 IrnBru, a carbonated soft drink, has been made available in refundable glass bottles. Consumers can return empty bottles to the retailer in exchange for either cash refunds or a credit voucher. In 2010, the deposit value was 30 pence, and an impressive 70% of bottles were returned, cleaned, and reused. In 2008, Environment Resources Management Limited found that deposit schemes increased return rates in the countries that used them, often to rates past 85%, and that they could also contribute to reductions in littering. Thus, designing policy around incentives and loss aversion has received support from the public and effectively increased recycling.

Related TDL Content

Why we need more than just a nudge

Nudging, the practice of influencing behavior to provoke a desired outcome, has been closely associated with the MINDSPACE framework. Take a look at this perspective article by Andrew Lewis on why nudging may not always be appropriate or sufficient, supported by COVID-19 examples.

Sources

- Dolan, P., Hallsworth, M., Halpern, D., King, D., Vlaev, I. (2010). MINDSPACE: Influencing behaviour through public policy. Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/MINDSPACE.pdf

- Dolan, P., Hallsworth, M., Halpern, D., King, D., Metcalfe, R., & Vlaev, I. (2011). Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(1), 264-277.

- Hallsworth, M., Egan, M., Rutter, J., & McCrae, J. (2018). Behavioural Government: Using behavioural science to improve how governments make decisions. The Behavioural Insights Team. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/BIT%20Behavioural%20Government%20Report.pdf

- The Behavioural Insights Team. (n.d.). About us. The Behavioural Insights Team. https://www.bi.team/about-us/

- Mols, F., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., & Staffens, N. K. (2015). Why a nudge is not enough: A social identity critique of governance by stealth. European Journal of Political Research, 54(1), 81-98.

- Sunstein, C. & Thaler, R. (2003). Libertarian paternalism is not an oxymoron. University of Chicago Law Review, 70(4), 1159-1202.

- Jones, R., Pykett, J., & Whitehead, M. (2010). Governing temptation: Changing behaviour in an age of libertarian paternalism. Progress in Human Geography, 35(4), 483-501.

- Rebonato, R. (2012). Taking liberties: A critical examination of libertarian paternalism. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- White, M. (2013). The manipulation of choice: Ethics and libertarian paternalism. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.