Intention-Action Gap

The Basic Idea

“My New Year’s resolution will be to exercise for 30 minutes a day, four times a week,” you think to yourself, eating holiday cookies on the couch and watching Love, Actually. Alas, December rolls around and you haven’t met the goal you set for yourself. Months pass, and you set a similar resolution the following January. Most people have experienced a similar cycle: setting an intention and not following through.

This intention-action gap, also known as the value-action gap or knowledge-attitudes-practice gap, occurs when one’s values, attitudes, or intentions don’t match their actions.1 Sometimes, the gap results from behavioral bias favoring immediate gratification. We may know that getting into a fitness routine will have long-term benefits, but watching the next episode of our favorite TV show is more gratifying in the moment. Alternatively, the intention-action gap can result from being too ambitious. We often intend to choose the “right” option, but something about our environment or the action itself can stop us from carrying it out.

Read more: Moving the Mental Goalposts: Why Aiming for the “Best” Isn’t Always the Best Strategy

One day you will wake up and there won’t be any more time to do the things you’ve always wanted. Do it now.

– Paulo Coelho, author ofThe Alchemist

Theory, meet practice

TDL is an applied research consultancy. In our work, we leverage the insights of diverse fields—from psychology and economics to machine learning and behavioral data science—to sculpt targeted solutions to nuanced problems.

History

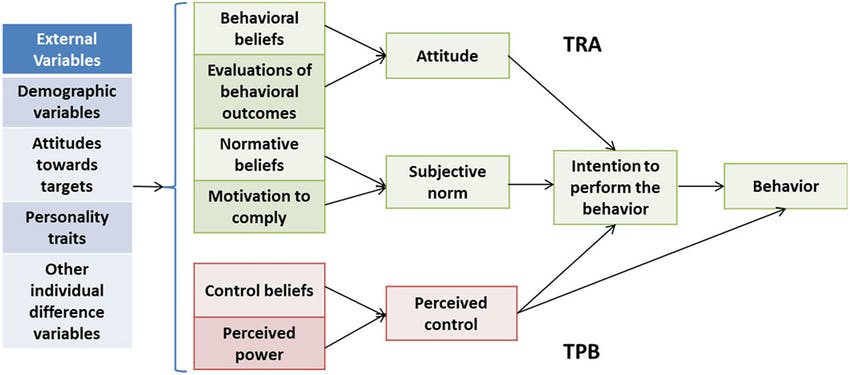

Research on human behavior has suggested how attitudes shape intentions, which subsequently shape actions.2 The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) rest on the assumption that behaviors are best predicted by intentions, which are shaped by attitudes about social norms regarding the behavior.

The TRA was developed by Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen in the late 1960s to better understand relationships between attitudes, intentions, and behaviors.2 The researchers distinguished between attitude toward objects (i.e. people don’t want cancer) and attitude toward behavior with respect to said object (i.e. people also often delay mammography). The two main factors of the TRA are:

(1) attitudes, based on one’s behavioral beliefs and evaluations of behavioral outcomes;

(2) subjective norms, based on normative beliefs and motivations to comply.

Together, attitudes and subjective norms influence one’s intentions to perform a behavior, which results in said behavior.

As an extension of the TRA, Fishbein and Ajzen developed the TPB in 1985. In their new model, they added the consideration of perceived control over performance of the behavior.2 In other words, the degree to which one believes they can control an outcome will influence their willingness to engage, regarding their general control beliefs and their perceived power in the situation. The TPB proposes that this perceived control, in conjunction with attitudes and subjective norms as outlined in the TRA, influences the intention to perform a behavior. Taken together, the TRA and TPB propose that behaviors should be correlated with intentions.

Researchers familiar with the TRA and TPB noticed that attitudes and intentions are not always strong predictors of behavior. The most obvious examples related to environmental protection: while people over time had reported increased awareness of issues such as global warming and high concern for the environment,3 there was no notable increase in pro-environmental behavior, such as recycling or limiting energy use.4 The observations of discrepancy between attitude/intention and behavior resulted in the study of the intention-action gap.

People

Martin Fishbein

Born in 1936, Dr. Fishbein is thought to be the pioneer of the Theory of Reasoned Action.5 Although he co-authored the TRA with Ajzen, it was Fishbein’s research that led to its development. Specifically, his work distinguished between attitudes toward an object, and attitudes toward a behavior with respect to said object. Fishbein’s work has been widely used in the fields of public health, psychology, communication, and advertising.

Icek Ajzen

Ajzen, social psychologist and professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, was born in 1942 and is best known for his work with Fishbein.6 Ajzen has been ranked as the most influential individual scientist within social psychology, in terms of cumulative research impact.7 His work has applied to health psychology, advertising, and environmental psychology.

Consequences

The intention-action gap has become one of the most studied topics in behavioral science since it can apply to so many different domains.1 The intention-action gap has become especially important for policy making, since a public awareness program may foster knowledge and intentions in individuals but individuals will still fail to follow through on their newfound intentions. Studying how people process information and how context affects behavior can help policymakers design more robust and effective interventions to which people will abide. The intention-action gap has been applied to areas such as environmental change,8 ethical consumptions,9 healthy behaviors,10 and even technology use.11

Importantly, acknowledging the prevalence of the intention-action gap has also spurred subsequent research on how we can eliminate it. Commitment devices are at the forefront of this literature.12

Implementation intention is a commitment device. It is a self-regulatory strategy, introduced by Peter Gollwitzer in 1999. Once a goal is set, implementation intention corresponds to, “I intend to perform behavior X when I encounter situation Y.” This way, people commit to a plan regarding when, where, and how they intend to work toward their goals. Control of the behavior transfers from the person to their situational context. Implementation intention implies an automatic behavior, therefore making it effortless and helpful for people struggling to translate their goals into behaviors. Additionally, commitment requires defining concrete goals and outlining a clear plan.

Communicating commitment to someone can be powerful due to the desire to maintain a positive self-image. Self-efficacy has also been suggested to address the intention-action gap: in essence, we should build people’s confidence in their abilities.13 By using evidence-based strategies that bridge the gap between intention and action, we can also improve our personal and professional lives.

Controversies

Criticisms surrounding the TRA and TPB are due to the theories’ roles in the conceptualization of the intention-action gap. Both theories were criticized by Neil Weinstein, a health psychologist and professor at Rutgers University, as part of a broader criticism on misleading theories about the process changing health behaviors (i.e. smoking, exercise).14 Specifically, Weinstein holds that many tests of these health behavior theories are based on correlational data, which are biased and cannot necessarily explain behaviors. Since the nature of correlational data can’t confirm causation or directionality, Weinstein posits that any tests that use correlational data tell us little about the theory’s validity. However, many published interventions since Weinstein’s criticism in 2007 have shown that changing factors of the TRA or TPB (i.e., normative beliefs, control beliefs, etc.) leads to subsequent change in behavior.15,16,17

Beyond Weinstein, other critics have called for retiring the TPB.18 For example, Sniehotta and colleagues hold that factors such as self-determination and anticipated regret predict future behavior better than perceived control. Thus, these researchers are concerned with the utility of the model: although the TPB theory led to identifying gaps between intentions and behaviors, new theoretical models should test phenomena that better help people change their behavior, rather than focusing on preventative factors.

Additionally, some critics hold that factors that influence the extent of the gap and its magnitude haven’t been systematically examined.19 Hassan and colleagues’ review of the literature found that specifically for ethical consumption, few studies had assessed both intention and behavior in context. As of 2014, there was limited empirical evidence to quantify the intention-action gap for ethical consumption.

However, Hassan and colleagues decided to do their own research on this matter, and conducted an empirical case study examining attitudes and behaviors toward sweatshop clothing. Results suggested a large gap between intention and action, with many participants proving an intention to consume ethically, but a lack of follow-through when it came to shopping. Additionally, empirical evidence in the domain of ethical consumption has grown since the Hassan’s original publication in 2014.20,21,22

Case Study

Clean drinking water

While the intention-action gap is frustrating in our personal lives, it can be fatal when it comes to sanitation and health, especially in developing countries. A case from 2010 showed how closing the intention-action gap can improve health and save lives, through increasing access to clean water using a behavior-led design.23 One of the simplest and most cost-effective ways to ensure clean drinking water in developing communities is to treat water with chlorine. However, adoption of chlorine treatments tends to be poor, as people either forget to do it or are unsure how to use it – an intention-action gap.

In response, behavioral scientist Michael Kremer led a team from Innovations for Poverty Action, tasked with designing a solution for a rural community in Kenya.23 The team needed to help communities embed chlorine use into their daily routines, and the chlorine needed to be easy to use. In other words, they needed to bridge the intention-action gap by increasing self-efficacy and making chlorine use an automatic process.

To make chlorine use an automatic and easy process, the team installed a dispenser at the local community water source. This way, the new purification behavior was linked to the already established routine of collecting water, a sort of “piggybacking” strategy. The team designed the dispenser bright blue so that it was salient. The location of the dispenser also made it effective because the required wait time for chlorine-treated water was partially automatically completed during people’s walk home.

An initial randomized controlled trial found that 50-61% of households with access to the dispensers adopted the chlorine treatment, compared to only 6-14% of the control group.23 Importantly, this effect was sustained over the two years from installation of the dispensers. The organization Evidence Actions has since scaled up this solution, providing access to clean water for 4 million people across Kenya, Malawi, and Uganda. Impressively, usage rates are still comparable, at over 50%.

Sustainable food consumption

An interest in sustainable production and consumption has increased at all levels of the agricultural chain. Farmers and consumers have learned that sustainable products can have positive benefits for economic profit, social wellbeing, and environmental sustainability.24 Ultimately, sustainable consumption is based on a decision-making process that considers the consumer’s social responsibility, as well as their individual needs and wants.

Everyday consumption practices are driven by convenience, habit, money value, and are likely resistant to change. A 2006 study by Vermeir and Verbeke found that although [young] people claim to be ethical consumers, actual ethical initiatives such as sustainable organic food and fair-trade products often have market shares of less than 1%. In other words, they identified an intention-action gap.

Sampling 456 consumers aged 19 to 22 years old, the researchers manipulated factors that influence consumer choice by showing advertisements for sustainable dairy.24 They found two factors that had a significantly positive impact on attitudes about buying sustainable products: the first was being involved with sustainability and the second was perceived consumer effectiveness. Both these factors were strongly correlated with intentions to buy sustainable dairy products.

Regarding involvement with sustainability, consumers are more influenced by their values than by the consequences of their actions. To this end, involvement or perceived personal relevance is a specific type of value that can motivate actions. Involvement is activated when a product, promotional message, or service is perceived as important for meeting one’s needs and values. To manipulate involvement, the researchers presented participants with an article describing the benefits of consuming sustainable products, such as increased safety, health outcomes, and improved taste.

Notably, perceived consumer effectiveness is related to perceived control in the TPB: it refers to the extent consumers believe their efforts or actions can contribute to solving the problem.

The availability of sustainable products influences how much control a consumer feels they have over their purchasing choices. In order to motivate behavioral changes, consumers must believe they are able to purchase sustainability, and that their actions will positively impact something that they value, such as the environment or fighting against social inequities. To manipulate perceived consumer effectiveness, participants were presented with informational messages about the availability of sustainable dairy products and how consumers could contribute to a better world.

The researchers suggested that low perceived availability of sustainable products might explain intention-action gaps. On the other hand, social norms tested through peer pressure were found to explain buying intentions; since it is the norm to buy traditional products, people tend to adhere through peer pressure. The results of the study showed that raising involvement, perceived consumer effectiveness, social perceptions, and perceived availability around sustainable food items can thus bridge the gap between intention and action for sustainable consumption. These findings have important implications for policy design and marketing strategies, as sustainability-focused organizations continue to address these factors in their interventions.

Related TDL Resources

Easing the Job Search During COVID-19

We’ve all heard that the job market during the pandemic has been virtually impossible to navigate successfully. Even in regular times, job searches are not easy. Take a look at this article that considers how setting an action plan – among other strategies – can bridge the intention-action gap and change your attitude toward job searching.

Mind the Gap (1/2): Environmental Behavior and Observed Consequences

While we may be attuned to the consequences of certain behaviors, we lack such awareness in other areas. Environmental consciousness typically yields a wide intention-action gap in the population. If you’re interested in reading further on how to influence behavioral changes as they relate to environmental consciousness, the bottom of the article contains a link to part 2!

Sources

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2017). Consuming differently, consuming sustainably: Behavioural insights for policymaking. http://www.ideas42.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/UNEP_consuming_sustainably_Behavioral_Insights.pdf

- Montaño, D. E., & Kasprzyk, D. (2008). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 67–96). Jossey-Bass.

- Banerjee, A., & Solomon B. (2003). Eco-labelling for energy efficiency and sustainability: A meta-evaluation of US programs. Energy Policy, 31(2), 109–123.

- Flynn, R., Bellaby, P., Ricci, M. (2009). The ‘value-action gap’ in public attitudes toward sustainable energy: The case of hydrogen energy. The Sociological Review, 57(2), 159-180.

- Ajzen, I. (2012). Martin Fishbein’s legacy: The reasoned action approach. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 640(1), 11-27.

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action-control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 1 l-39). Heidelberg: Springer.

- Nosek, B. A., Graham, J., Lindner, N. M., Kesebir, S., Hawkins, C. B., Hahn, C., Schmidt, K., Motyl, M., Joy-Gaba, J., Frazier, R., & Tenney, E. R. (2010). Cumulative and career-stage citation impact of social-personality psychology programs and their members. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(10), 1283–1300.

- Kennedy, E. H., Beckley, T. M., McFarlane, B. L., & Nadeau, S. (2009). Why we don’t” walk the talk”: Understanding the environmental values/behaviour gap in Canada. Human Ecology Review, 151-160.

- Hassan, L. M., Shiu, E., & Shaw, D. (2016). Who says there is an intention–behaviour gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(2), 219-236.

- Mohiyeddini, C., Pauli, R., & Bauer, S. (2009). The role of emotion in bridging the intention–behaviour gap: The case of sports participation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(2), 226-234.

- Bhattacherjee, A., & Sanford, C. (2009). The intention–behaviour gap in technology usage: The moderating role of attitude strength. Behaviour & Information Technology, 28(4), 389-401.

- Adam, A. F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). Bridging the entrepreneurial intention–behaviour gap: The role of commitment and implementation intention. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 25(1), 36-54.

- Sniehotta, F. F., Scholz, U., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). Bridging the intention-behavior gap: Planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychology & Health, 20(2), 143-160.

- Weinstein, N. D. (2007). Misleading tests of health behavior theories. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(1), 1-10.

- Jemmott, J. B. (2012). The reasoned action approach in HIV risk-reduction strategies for adolescents. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 640(1), 150-172.

- Johnson, B. T., Scott-Sheldon, L. A., Huedo-Medina, T. B., & Carey, M. P. (2011). Interventions to reduce sexual risk for human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents: a meta-analysis of trials, 1985-2008. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(1), 77-84.

- Mosleh, S. M., Bond, C. M., Lee, A. J., Kiger, A., & Campbell, N. C. (2014). Effectiveness of theory-based invitations to improve attendance at cardiac rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 13(3), 201-210.

- Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J., & Auraújo-Soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychology Review, 8(1), 1-7.

- Hassan, L. M., Shiu, E., & Shaw, D. (2016). Who says there is an intention–behaviour gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(2), 219-236.

- Jacobs, K., Petersen, L., Hörisch, J., & Battenfeld, D. (2018). Green thinking but thoughtless buying? An empirical extension of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy in sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 203, 1155-1169.

- Longo, C., Shankar, A., & Nuttall, P. (2019). “It’s not easy living a sustainable lifestyle”: How greater knowledge leads to dilemmas, tensions and paralysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(3), 759-779.

- Dermody, J., Koenig-Lewis, N., Zhao, A. L., & Hanmer-Lloyd, S. (2018). Appraising the influence of pro-environmental self-identity on sustainable consumption buying and curtailment in emerging markets: Evidence from China and Poland. Journal of Business Research, 86, 333-343.

- Kremer, M., Miguel, E., Mullainathan, S., Null, C., & Zwane, A. P. (2011). Social engineering: Evidence from a suite of take-up experiments in Kenya. Unpublished Working Paper.

- Vermeir, I., & Verbeke, W. (2006). Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 19(2), 169-194.